As some of my friends know, my mother is a hard-core Wodehouse pusher. She has a collection of used Wodehouse paperbacks specifically for getting people hooked (the first-edition hardback library doesn't leave the house, not even in the hands of immediate family). She keeps a framed picture of Wodehouse and his Dachshunds on the bookshelf in the study, with the rest of the family portraits; a list of all the Wodehouse books she already owns on her iPod nano so she doesn't double-purchase; and she has instructed the Duvall Used Bookstore to call her as soon as they get any Wodehouse in stock.

As some of my friends know, my mother is a hard-core Wodehouse pusher. She has a collection of used Wodehouse paperbacks specifically for getting people hooked (the first-edition hardback library doesn't leave the house, not even in the hands of immediate family). She keeps a framed picture of Wodehouse and his Dachshunds on the bookshelf in the study, with the rest of the family portraits; a list of all the Wodehouse books she already owns on her iPod nano so she doesn't double-purchase; and she has instructed the Duvall Used Bookstore to call her as soon as they get any Wodehouse in stock.Once, before she was on the call list, she went to pick up my younger brother Adam from a friend's house in rural Woodinville. As they pulled out of the neighborhood, she felt she just HAD to go to the Duvall Bookstore. In spite of Adam's grumbling, she turned left instead of right and headed to Duvall...she just knew there was a Wodehouse on the shelf for her. She parked right in front of the door, and three minutes later she was back in the car with a $10 first edition. Adam was impressed enough to quit bellyaching, and we haven't doubted her supernatural abilities since.

So what is there to know about Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (or "Plum," as his friends called him)? He lived from 1881-1975 and in that time wrote ninety-six books, fifteen plays, some lyrics for about thirty musicals (like Anything Goes and Show Boat) and various screenplays. In 1939, he was living in France, and didn't bother leaving when the war broke out, as he wasn't very politically savvy. The Germans imprisoned him in 1940; he was interned in Belgium and later in Upper Silesia (now in Poland). His response was "if this is Upper Silesia, one wonders what Lower Silesia must be like..."

Because of his distance from Britain and its wartime experience, Wodehouse didn't entirely grasp the severity and somberness of the national mood. After being released, he recorded a series of radio broadcasts for the Germans about his internment. In retrospect, it is clear that he was just trying to be jolly--the tone is light and pokes fun at the Germans, and reflects the plucky morale of the Brits with whom he had shared his internment time. Goebbels, et al, however, knew Wodehouse's tone and depiction would come across as good P.R. for the Germans, and they played on his naivete.

In a cable to the editor of the "Saturday Evening Post," who had mentioned Wodehouse seemed "callous about England" in his broadcast, Wodehouse responded, "Cannot understand what you meant about callousness. Mine simple, flippant, cheerful attitude of all British prisoners; it was a point of honour with us not to whine." However, there was a huge and wrathful backlash in Britain: he was labeled a spy and a traitor in the press, accused of being a Hitler sympathizer, and the BBC banned all his work. A.A. Milne was one of his major critics, though both George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh came to his defense. Wodehouse was even investigated by MI5, and only in 2006 did they release the files clearing him of any wrongdoing. Wodehouse and his wife Ethel moved to New York after the war, deterred from going home by the seething dislike that was waiting for them, and by the fact that Leonora, Ethel's daughter and Wodehouse's step-daughter, died during surgery in London in 1944. He lived in the United States for the rest of his life.

His most famous characters are, of course, Bertie Wooster and his butler Jeeves, played to my extreme satisfaction by Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry on the BBC and Masterpiece Theatre, long before both Fry and Laurie began popping up in shows on FOX. The Blandings Castle stories are also popular, about the daffy Lord Emsworth, his family, and his pig the Empress. Mr. Mulliner stories identify the characters not by name but by what they drink (i.e., Hot Scotch and Lemon). There are plenty more, and an overview can be found here. His writing style is wry and clever, rife with puns and bumbled situations, and characters named Freddie Threepwood and Gussie Fink-Nottle. However, he isn't the type to preen--reading his work, you can tell he just delights in being able to tell jokes, and he wants more than anything to make his reader happy. I emphatically encourage you to dabble in some Wodehouse. Carry On, Jeeves, a collection of short stories from 1928, is a wonderful gateway book. Plum (and my mother) just want you to be happy...won't you give in?

In the hope that you might, I'll leave you with some of Wodehouse's best one-offs:

And perhaps the best book dedication in literature, from The Heart of a Goof (UK, 1926):Freddie experienced the sort of abysmal soul-sadness which afflicts one of Tolstoi’s Russian peasants when, after putting in a heavy day’s work strangling his father, beating his wife, and dropping the baby into the city reservoir, he turns to the cupboard, only to find the vodka bottle empty.

Jill the Reckless, 1921

He, too, seemed disinclined for chit-chat. We stood for some moments like a couple of Trappist monks who have run into each other by chance at the dog races.

Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, 1954If not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.

The Code of the Woosters, 1938

He was in the acute stage of that malady which, for want of a better name, scientists call the heeby jeebies.

Spring Fever, 1948

TO

MY DAUGHTER

LEONORA

WITHOUT WHOSE NEVER-FAILING

SYMPATHY AND ENCOURAGEMENT

THIS BOOK

WOULD HAVE BEEN FINISHED

IN

HALF THE TIME

MY DAUGHTER

LEONORA

WITHOUT WHOSE NEVER-FAILING

SYMPATHY AND ENCOURAGEMENT

THIS BOOK

WOULD HAVE BEEN FINISHED

IN

HALF THE TIME

4 comments:

What fun this was to read! Thanks for the chuckles! Great blog.

PGW Fan

Hallo Rebecca,

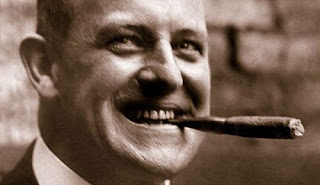

Let me first ask you if this chappie with the big cigar is PG Wodehouse?

I am a great admirer of him and own all the Jeeves/Wooster stories plus

Psmith.

What would you advice to read next??

Thanks in advance

Georg

Georg--

If you've done Jeeves and Psmith, you should definitely check out Blandings Castle. There is a collection that actually features both Blandings short stories and Mr. Mulliner short stories; it is called simply Blandings Castle. That would be a good jumping-off point!

Thanks for reading!

Oh, and yes: the cigar chappie is a young Plum. He got much foldier around the gills in his later years, understandably.

Post a Comment